Giza & Sakkara Pyramids • Felucca • Museum • Coptic Cairo • Islamic Cairo • Citadel

Day One: Giza & Sakkara Pyramids • Felucca

Giza Plateau

The Great Pyramid of Khufu…4,500 years old, the oldest and last remaining of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the tallest building on the planet for 3,800 years, enough stone to build a 3 metre high wall around France (according to Napoleon)…what more is there to say? The countless volumes dedicated to this monument cannot hope to prepare you for its jaw dropping magnificence; you’ll just have to see it for yourself! *Additional ticket required Other optional extras at Giza include: the interior of the Great Pyramid of Khufu, 2nd/3rd pyramid and camel/horse and cart ride.

Sakkara

Necropolis of the ancient capital of Memphis for 3000 years, Sakkara is the final resting place of pharaohs, nobles, family members and sacred animals.

Sakkara’s most obvious attraction is the Pyramid of Zoser: constructed by Imhotep in 27 BC, it broke the tradition of burying royals in underground rooms or single mud-brick mastabas and was the inspiration for the architectural masterpieces that followed. Imhotep took a simple mastaba and added to it 5 times (taking it to a height of 62m) before encasing in white limestone; its outer casing is long gone (quarried for Cairo’s palaces and mosques) but the world’s oldest large-scale cut stone monument is still a hugely impressive sight. The pyramid is the outstanding feature of Zoser’s huge (544m x 277m) mortuary complex; excavation and restoration are ongoing but plenty of fascinating fragments remain, including: a large section of the original bastioned and panelled boundary wall, the vestibule, a colonnaded corridor and broad hypostyle hall, the Great South Court with a rebuilt section of wall featuring a frieze of cobras (protector of the King) and 2 stone altars representing the thrones of Upper and Lower Egypt – used during the 30th year of the king’s rule to re-enact his coronation and renew his rule. Sakkara is also home to: Please note that time doesn’t permit us to include all Sakkara’s attractions in our standard tour day though we’re always happy to extend. *Additional ticket required

Felucca

End your day with a relaxing one hour cruise in a felucca. These ancient sail boats have been plying their trade on the Nile since Ramsis was a boy – the landscape has changed a great deal since then but the soothing effect of the river has not.

Day Two: Museum • Coptic Cairo

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities

Barely altered since its establishment in 1902, the Egyptian museum is badly organised and its contents poorly displayed (and due to be replaced by the the Grand Egyptian Museum in 2020) but the sheer quantity and quality of unique ancient Egyptian artefacts make it a must see.

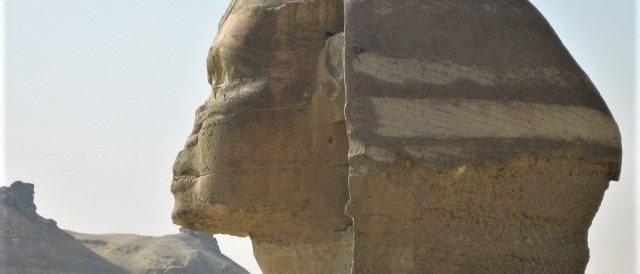

Every period of ancient Egypt (up to and including Graeco-Roman) is represented here and the 120,000+ relics include larger than life statuary, mummies*, tomb contents, sphinxes, sarcophagi and jewellery.

The real highlight though is the Tutankhamun exhibit: around 1700 items spread over several rooms display the stunning contents of this young and (until his burial site was discovered in 1922) insignificant king’s tomb. *Please note that an additional ticket is required for the Royal Mummies exhibit

Coptic Cairo: Mar Girgis

The oldest part of modern-day Cairo and heartbeat of Egypt’s Christian community, this tightly walled enclosure is an oasis of peace and tranquility and a welcome contrast to the chaos on its borders. Evidence exists of a 6th century BC Persian fort in the area, the site of which became the foundation for a 2nd century BC Roman fortress named Babylon-in-Egypt. The remains of the two round towers of Babylon’s western gate now form the entrance to the compound which is home to several ancient churches, the only synagogue open to the public in Egypt and a museum.

Saint Virgin Mary’s Coptic Orthodox Church (4th century AD)

More popularly known as the Hanging Church due to its placement on top of the Water Gate of Roman Babylon, this is the most famous and probably oldest Christian site of worship in Cairo.

The interior is beautifully decorated and has 3 barrel-vaulted, wooden-roofed aisles, an ivory inlaid screen and a pulpit raised on 13 slim pillars depicting Christ and his disciples – the darkest of which symbolises Judas. A panel in the floor of the baptistry gives a rather gloomy snapshot of the Water Gate below – take a look out of the window for a better view of one of the gate’s twin towers.

Other churches:

Ben Ezra Synagogue (882)

Built on the remains of a 4th century basilica and originally named the ‘synagogue of the men of Israel’, this structure – like so many in Mar Girgis – has been restored and rebuilt several times, most significantly in the 12th century by the Rabbi of Jerusalem from whom it now takes its name. A number of legends are associated with the synagogue. There is a spring which is said to mark the spot where Moses was found in the reeds and where Mary drew water to bathe Jesus. This is also the supposed site of the prophet Jeremiah’s temple and the place in which he gathered the Jews after Nebuchadnezzar had destroyed their temple in Jerusalem.

The Coptic Museum*

Founded in 1908, the museum is home to the world’s largest collection of Coptic art and artefacts. The approximately 15,000 Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman relics date from the Graeco-Roman to Islamic era and are drawn from Cairo, the desert monasteries and Nubia. Items include stone, wood and metalwork, textiles, glass and ceramics and the rooms’ mosaic floors, old mashrabiya screens and beautifully decorated ceilings are a significant part of the museum’s attraction.

*Additional ticket required

Coptic Cairo: Cave Churches of Mokattam • Garbage City • eL Seed ‘Perception’ Mural

‘Garbage City’ is home to the ‘Zabaleen’ (rubbish collectors) who can justifiably lay claim to one of the most efficient recycling systems in the world: over 90% of the approximately 4000 tons of domestic waste (40% of the city’s output) they handle on a daily basis is recycled – compared to 56% in Germany, 45% in the UK and 35% in the US – an astonishing achievement for an informal (and largely self-funded) system. It’s a fascinating, if not necessarily pretty, area to drive through and the APE (Association for the Protection of the Environment) centre and shop is well worth a visit on your way to the Cave Churches.

The Cave Churches of Mokattam

These grand ‘structures’ tucked into the caves of the Mokattam hills are a remarkable testament to what can be achieved by a dedicated community in the face of adversity – whether it be resisting authority or overcoming the enormous challenges posed by building in such an unfavourable location.

The first church in the village (a simple tin construction) was built in 1975 but swiftly supplanted by the first of the cave churches after a fire destroyed much of the area’s housing a year later. Preparing the site for its new purpose was no mean feat: the cave that now houses the Virgin Mary and St. Simon the Tanner Cathedral was a mere 1 metre high and 140,000 tons of stone and debris was removed from the St. Simon the Tanner Hall and St. Mark’s church caves. The vast majority of clearance and excavation was carried out by hand; a massive undertaking that involved the entire community and took several years to complete. There are now seven churches in the area, the largest of which is the Cathedral of St. Simon the Tanner – indeed its capacity of 20,000 also makes it the largest in the Middle East. The caverns and surrounding cliffs are adorned with stone engravings depicting bible scenes, many of which were carved by Mario, a Polish national who moved to Cairo in the late 1990’s – just one of the many individuals who have made it their life’s work to give the Zabaleen and wider Coptic community a truly majestic place of worship.

The eL Seed ‘Perception’ Mural

This massive fusion of calligraphy and graffiti covers 50 buildings and was completed in March 2016 by the French-Tunisian artist eL Seed; possibly just as impressive as the artwork itself is the fact that it was done under the noses of the local authorities without their knowledge! The mural is dedicated to the Zabaleen community and reads: “Anyone who wants to see the sunlight clearly needs to wipe his eye first.”

Day Three: Islamic Cairo • Citadel

Islamic Cairo: Sharia Mu’izz li-Din Allah & Khan al-KHalili

Sharia Mu’izz li-Din Allah & Khan al-Khalil

‘Mo’ezz Street’ to Cairenes was the city’s grand mediaeval thoroughfare and takes its name from the Fatimid caliph who conquered Cairo in AD 969. Much of the street has been sensitively restored and is now a superb showcase for the greatest collection of mediaeval architecture in the Islamic world.

There are scores of scheduled monuments on and around the street – dating from 970 through to the middle of the 19th century – too many for a short tour but here’s a few favourites to choose from:

Please note that an additional ticket is required to view monument interiors

Bab al-Futuh (Gate of Conquests, 1087)

This monumental gate opens onto Sharia Mu’izz li-Din Allah and is one of three remaining (there were originally eight) main entrances to the newly built Fatimid city of Al-Qahira. It is linked to Bab an-Nasr (Gate of Victory) via a section of the original city wall and a few minutes in and along the gates and walls will give you a very good idea of the scale of this impressive piece of military architecture.

Beit el-Suhaymi (1648, extended 1796)

The best example of an Ottoman house in Cairo is just a few steps down a side street off Sharia Mu’izz. Its recent restoration has left it feeling a little sparse but it’s beautifully decorated and gives an authentic impression of the habits and lifestyle of the wealthy during the Ottoman era. The central courtyard of this mansion and caravanserai is flanked by approximately 30 chambers; strictly segregated between the Salamlik and Haramlik and include grand reception halls, bedrooms, bathrooms, storerooms and a takhtabush. The house provides an excellent insight into the climate control methods utilised (by the wealthy at least) before the advent of air-conditioning: the courtyard retained and diffused cooler night air into rooms during the day while a domed aperture in the centre of the reception provided an outlet for warm air. These were augmented by a fountain below the dome, high ceilings, marble floors, mashrabiya screens and a malqaf that distributed cold air to the inner chambers. The house is also a creativity centre and hosts a number of activities that seek to preserve Egypt’s musical and cultural traditions.

Sabil–Kuttab of Abdel Katkhuda (1744)

This iconic and exquisite little building fulfilled humble but essential purposes: a sabil is a public drinking fountain, a kuttab a Quranic school and their combination provided two things extolled by the Prophet – i.e. water for the thirsty and spiritual instruction for the unenlightened. The structure blends Mamluk and Ottoman styles and is beautifully decorated with ornamented vaulting, polychrome marble, mashrabiya and glazed ceramics.

Bein al-Qasreen (Between the palaces)

Once the site of two Fatimid royal palaces, the area immediately south of the sabil–kuttab is now occupied by three great Mamluk complexes which form one of Cairo’s (or anywhere else for that matter) most remarkable assemblies of Islamic architecture .

Madrasa & Mausoleum of Sultan al-Zahir Barquq (1386)

Barquq was the first of the Circassian or Burji Mamluks who seized control from the Bahri Mamluks in 1382 while Egypt was gripped by plague and famine.

Fearful of an insurgency by supporters of the previous regime, Barquq sought to validate his administration by marrying Baghdad Khatun, widow of Sultan Sha’ban (one of the last descendants of Qalawun) and commissioning his funerary foundation next to the earlier Qalawunid complexes. In common with most Mamluk complexes, Barquq’s foundation served several functions: a Friday mosque, madrasas that taught the four schools of (Sunni) Islamic jurisprudence and a khanqah – a place of spiritual retreat for Sufis. A bronze door, adorned with geometric stars and framed in striking black and white marble, opens onto a vaulted passageway which leads to a cruciform courtyard. The courtyard, with marble mosaic paving and central ablution fountain, (with an ornate wooden dome supported by eight marble pillars) is flanked by four iwans with large pointed arches and carved stone inscriptions. Unlike most other 14th century mosques, the octagonal shaft of the minaret is carved, with intersecting circles and white marble inlays. The interior is equally impressive and features an elaborately painted and gilded ceiling, a qibla decorated with a marble dado and a marble prayer niche. The mausoleum (note that it isn’t Barquq who lies here but his daughter – he is interred in the Northern Cemetery) is accessed via a door on the north side of the prayer hall and has typically ornate painted wooden pendentives and stained glass windows.

Mausoleum of al-Nasir Mohamed (1303)

The youngest son of Qalawun’s reign was a particularly turbulent one even by Mamluk standards (his reign was interrupted twice) but it also marked the high point of Mamluk power and culture. Public works commissioned during his reign include the aqueduct from the Nile to the Citadel, a canal reconnecting Alexandria with the Nile, the renovation of 30 mosques, the first sabil in Cairo, the renovation of at least 30 mosques and this mosque and madrasa next door to his father’s. The complex has two outstanding features: the Gothic doorway, consisting of a triple recessed pointed arch and framed by three slender columns, is carved from a single piece of white marble. This elegant portal is also of historic significance; taken from Acre after al-Ashraf Khalil’s (al-Nasir’s older brother) defeat of the Crusader armies there, it is a highly prized trophy of the long series of vicious religious wars between the Roman church and the Muslim rulers of the Holy Land. The elaborate lower section of the minaret is one of the few remaining stucco minarets in Cairo and has exquisitely carved decorations of medallions, geometric and floral patterns, keel-arched niches and bands of Kufi and Thuluth scripts.

Madrasa and Mausoleum of Qalawun (1279)

If you have time to explore just one of the three complexes in Bein al-Qasreen, make this it.

This huge development was completed in just 13 months and marked a new phase in Islamic architectural design. The tradition of erecting single structures with a sole purpose was abandoned in favour of building ‘complexes’ that typically included more than one architectural element and served a number of functions – Qalawun’s included a madrassa, mausoleum and maristan which tended to the city’s sick until being demolished in 1910. The mausoleum, considered to be the second most beautiful after the Taj Mahal, is a stunning confluence of mashrabiya, mother of pearl, granite pillars and stone and stucco carved with stars and floral patterns. The mihrab, adorned with marble and mother of pearl, is one of the largest and most lavish in Egypt and this magnificent assembly is beautifully lit by stained glass windows. The dome was especially significant as it served as a ceremonial centre in which new emirs were inducted and was therefore seen as a symbol of new power. The madrasa, which taught the four Sunni schools of thought, originally consisted of a central open courtyard flanked by four iwans. Sadly little remains of this structure except for the qibla iwan which opens onto the courtyard via three large arches. The maristan was particularly close to Qalawun’s heart: modelled on the Damascus hospital that saved his life while in the Sham region, the institution supplied medical treatment, shelter, food and clothing to the poor and infirm for over 600 years. The 1910 demolition left a few hints of the hospital’s grandeur – the best of which is a finely decorated marble fountain.

Khan al-Khalili

The Khan’s stallholders now trade with tourists rather than Ottoman merchants, but its 16th century layout, architecture and centuries of hustle and bustle make it an authentic Arabian souk. You can find just about anything in its twisting narrow alleys, from silver, gold, precious stones, perfume and spices to backgammon boards, plastic pyramids and stuffed camels. The sales patter (“look for free”, “no hassle” and “special price”) may jar at times but it’s all good natured and haggling is expected as well as being part of the fun.

Al-Ghuri Complex and Wikala (1505)

The huge complex straddling Sharia Mu’izz just south of the Khan is an appropriately grand monument to the end of over 250 years of turbulent Mamluk rule.

Qansuh al-Ghuri, the penultimate Mamluk sultan (and last to wield any significant power) died whilst fighting the Ottoman Turks outside Aleppo in 1516. Al-Ghuri’s body was never found and his mausoleum is the final resting place of his short-lived successor Tumanbey, whose capture and death a year later heralded the dawn of Ottoman rule. The complex includes a Friday mosque-madrasa, khanqah, mausoleum and sabil–kuttab, their facades don’t follow the street alignment but instead broaden to form a skewed square which was then (and now) roofed and rented out to stallholders to help pay for its upkeep. The mosque-madrasa’s design was undoubtedly influenced by Qaitbey’s mausoleum and madrasa in the City of the Dead though, whilst built on a larger scale, it lacks the former’s exquisite detail and reflects the decline in Mamluk power and culture. Nevertheless, to my eyes it’s still pretty splendid with a central open courtyard, four iwans, gilt, painted and black and white marble panels, floors laid in geometric patterns and polychrome marble dados. Al-Ghuri’s nearby wikala was restored as recently as 2004 and is one of the most impressive of its type in Cairo. The five storied building was constructed around a large courtyard with elaborately patterned marble fountain; it housed animals on the ground floor and merchants on the first while the three upper floors (the highest of which are adorned with some of Cairo’s finest mashrabiya) formed a complex of low-income apartments. The building now serves as a cultural centre and, as well as being home to various arts and crafts studios, is the venue for the Al Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe who perform their spectacular Sufi dance every Monday, Wednesday and Saturday. South of Al-Ghuri, Mu’izz becomes a busy market in which household goods and clothing (pick up a galabiyya?) are sold – not of huge interest but it’s also where you’ll also find Cairo’s last tarboosh (fez) maker. The days when every respectable effendi (gentleman) wore one are long gone but it’s worth a few minutes of your time to watch them work the hats into shape on the heavy brass presses before heading down towards Bab Zuweila.

Mosque of al-Mu’ayyad (1422)

A notorious schemer, Al Mu’ayyad Seif ad-Din was thrown into a lice-infested prison in which his suffering was so great he vowed (if he were ever to be freed) to transform the site into “a saintly place for the education of scholars”. Al-Mu’ayyad was not only freed but also became sultan and, true to his word, demolished the prison and replaced it with this mosque-madrasa built adjacent to and (in the case of the two minarets) above Bab Zuweila. This was the last great hypostyle mosque built in Cairo and owes much of its grandeur to the sultan’s talents for thievery: existing structures were robbed of marble, columns and a beautiful 10th century panel of Kufic script. The ‘reusing’ of al- Hussein’s monumental door (a masterpiece of Mamluk metalwork) and chandelier was a particularly nefarious deed as removing items from functioning mosques was illegal at the time. The minarets provide one of the best views in Cairo; take in the contours of the medieval city whilst marvelling at the rooftop facilities – used as pigeon lofts, workshops, goat pens, chicken runs and rubbish dumps.

Bab Zuweila

The only remaining southern gate of the medieval city, Bab Zuweila’s history is a little grimmer than its northern counterparts. This was one of the main public meeting places during the Mamluk era, largely atributable to the fact that it was the site of executions which were a highly popular form of street theatre. Hundreds would gather to witness the Mamluks’ gruesome displays of slaughter which included publicly sawing the condemned in half or crucifying them on the great wooden doors. Lovely. The gate’s reputation for brutality was softened a little by its association with a 19th century saint, Metwalli, who lived nearby. Those in need of healing or divine intervention would nail a lock of hair or piece of clothing to the door in the hope of attracting his attention and aid. The practice continues and to this day a fresh nail is occasionally hammered into the ancient timbers.

Islamic Cairo: Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Hassan (1356-63)

One of the finest examples of early Mamluk architecture in Cairo and one of the largest mosques in the world, this innovative structure is both mosque and madrassa (theological school) with four iwans each devoted to one of the main schools of Sunni Islam: Shafi’i, Maliki, Hanafi and Hanbali. The monumental entrance, itself a work of art, leads to a large courtyard, in the centre of which is a domed ablutions fountain. The beautifully decorated vaulted iwans line the courtyard and, in addition to a madrassa, each had their own courtyard and four floors of student/teacher accommodation. Other features to note are the unusual egg shaped dome, beautiful mihrab, (flanked by stolen Crusader columns) construction material (wood) and the use of chinoiserie – the only known example in Mamluk architecture.

Islamic Cairo: Mosque of al-Rifai (1912)

The relatively modern mosque adjacent to Sultan Hassan’s was built in Mamluk-style as part of an attempt by Egypt’s 19th century monarchy to associate themselves with perceived former glories. No expense was spared during construction and the huge marble columns, acres of marble, (19 types from 7 countries) beautifully carved mashrabiya, elaborate ceilings and one of the most beautiful minbars you’ll ever see more than adequately compensate for the lack of history and pedigree in comparison to its more venerable neighbour. Built on the site of site of the tomb of Rifai, (a medieval saint who was re-buried here) the mosque is also the last resting place for several members of Egypt’s last royal family and the last Shah of Iran.

The Citadel of Salah ad-Din (1176-83)

Saladin’s (he of Crusader fame) sprawling medieval fort on the eastern edge of the old city was the seat of government for over 700 years. Now home to three mosques and five distinctly average museums it’s a great place to catch a bit of welcome breeze and take in some of the best views in Cairo.

The dominant feature is the mosque of Mohamed Ali, built 1830 – 48 and modelled on the Sultan Ahmed mosque in Istanbul, it’s not the most significant or beautiful of Cairo’s many mosques but it undoubtedly occupies the most prominent position. The Mosque of an-Nasir Mohamed (1318) is the Citadel’s sole surviving Mamluk structure, (all others were destroyed by Mohamed Ali) it’s a little sparse due to its stripped marble (thanks to sultan Selim I, first Ottoman sultan of Egypt) but the twisted finials of the minarets are interesting for their glazed tiles – rarely seen in Egypt. The Mosque of Suleiman Pasha (1528) is small but beautiful, built during the Ottoman era and topped by a cluster of domes, the interior woodwork has been recently restored by a local art student. * Please note that additional tickets are required for the mosques of an-Nasir Mohamed and Suleiman Pasha and museums.